A new sight in a new place

When we first visited Lewiston and Clarkston at Thanksgiving in 2023, we didn’t know what to expect. The landscape of the area surprised us. The towns sit in a valley, where the Clearwater River, flowing west, meets the Snake River, flowing east, and the Snake continues south. Lewiston sits on the east side of the river. Clarkston is on the west. The boundary between Idaho and Washington is at the middle of the river.

Lewiston is on the left side of the river, Clarkston is on the right.

What both towns share is a view of steep hills to the north. These hills, known as “The Palouse”, stretch east and west as far as the eye can see.

My first impression was that the hills looked like an alien planet. (I had watched “Interstellar” on the flight over and had far-off worlds on my mind.) The hills appeared to be harsh and inhospitable, steep and rocky. It was disturbing.

Now, a year later, we live here. Our views have been tempered by the constant presence of the hills. You can see them from almost any place in either town. Their appearance changes almost every day, depending on whether the sun is shining or it’s cloudy. A feature of many of the homes we looked at was a view of the hills. Our own home has a partial view, more so now that leaves have fallen off the trees.

But we’re still curious about how this unusual landscape came to be.

How the Palouse was formed

The geologist and geographer John A. Alwin provided a detailed, and very readable, explanation of the history of the Palouse in his book Between the Mountains: A Portrait of Eastern Washington.1 According to Dr. Alwin, the rolling hills of the Palouse were formed in three stages.

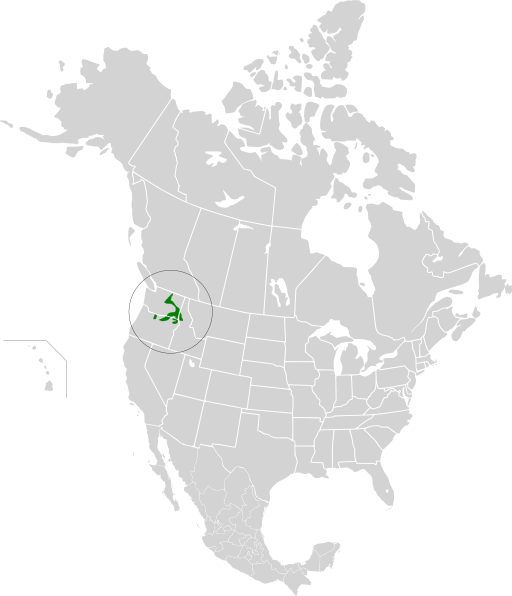

Image credit: Cephas on Wikimedia Commons

The first stage took place over millions of years during the latter part of the Miocene era (23 million to 5 million years ago). Underground volcanic activity forced basalt lava out of fissures in the earth. These “flood basalts” flowed across the plains of what is now eastern Washington, northern Idaho, and northern Oregon, sometimes at speeds of up to 30 miles an hour.

The “Columbia River basalts”, as geologist today know them, covered an area of about 50,000 square miles. Over millions of years, the layers piled up, sometimes reaching a height of 300 feet, with underground layers up to two miles thick.

The second stage happened during the Pleistocene Epoch (2.6 million to 12,000 years ago). Wind-blown silt, known as loess, covered the lava bed. In this area, the Palouse Loess had accumulations of up to 300 feet deep and formed the rolling hills we now see.

In the final stage, also in the Pleistocene Epoch, rich soil developed on top of the loess.

Photo by Caleb Riston on Unsplash

The Palouse today

This is an agricultural region that is sparsely populated. Driving across the Palouse, you can go miles without seeing a house. A lesson we learned early on is that if you’re traveling in the region, don’t expect to find gas stations, toilets, or restaurants anytime soon.

The soil in the Palouse is incredibly fertile, and agriculture developed in the region from the mid-1800’s until today. The Palouse is one of the most productive wheat-growing regions in the world. According to the Washington Grain Commission

The playing surface of a football field is about an acre. About 2.24 million football fields of wheat were harvested in Eastern Washington in 2024, which is the same as in 2023 and down slightly from 2.27 million football fields in 2022.

In addition to wheat, 30% of the world’s lentils are grown in this area. Also canola, barley, and onions.

A modern day problem, and threat to the Palouse, is erosion. In cultivated areas, water running off the rolling hills carries away topsoil. A study by Washington State University noted that erosion rates of up to 200 tons per acre (more than 1 inch of topsoil) were common on steep slopes and that as much as three feet of topsoil has been lost from hilltops and ridges due to tillage.

Multiple techniques have been adopted over the last 40 years to help prevent erosion, including no-till and minimal-till planting, crop rotation. Some farmers have even begun growing Kentucky Bluegrass, a crop that controls erosion and offers some income.

Going “Up the hill”

A phrase we hear often is “we’re going up the hill”, which means driving north out of Lewiston towards Moscow, Idaho or Pullman, Washington. These slightly larger towns are home to two land-grant universities – The University of Idaho (founded 1889 – Go Vandals!) and Washington State University (founded 1890 – Go Cougars!). We’ve visited Moscow a couple times, but haven’t been to Pullman since last year.

We have a lot of exploring to do!

When we first arrived in Lewiston, the Palouse hills were brown and bleak. As winter approaches, they are greening up and if we look closely, we can see cattle grazing on the slopes. We’re looking forward to seeing what other changes occur as the year progresses.

Until next time,

Mary and Mike

The Cook and The Writer

What unusual geological feature is found near where you live? Leave your observations in the comments below or via the Contact Us form.

- This link is direct to AbeBooks.com, but we do not receive any affiliate payment if you buy a copy. If that changes in the future, we’ll let you know. ↩︎

I spent some time in that part of the US and thought it was fascinating. The drive from Seattle to that area is a beautiful drive as well.

What a fascinating take on where you are now living. I loved the movie “Interstellar” and can see how it influenced your thoughts on the landscape. Now, to get down to serious business, what have you discovered about the food in the area?

I have traveled a lot, but never have seen a place like this. The huge spaces, the particular nature that does not give much space to the trees, the colors that change according to the seasons. These photos that you have published have left a vivid impression on my mind. I absolutely must visit this area of the USA. A hug to all of you

I love how curious you are about the places you are in. Fascinating!!

Wow, what a fascinating landscape and wonderful photos. Feliz dia de peru para ti e Mary!

Two thoughts instantly came to mind as I read your post. 1. I will never understand how a geologist can look at some rock and stone and figure out what happened 1million years ago. Yes, there is a reason I was a liberal arts major. 2.I can imagine Mary collecting fertile soil at the base of the hill for your future garden. Happy holidays!