Time to Learn Something New

Not long ago, I ran across an article that mentioned a list of “classic travel writers, people like Jan Morris, Ryszard Kapuscinski, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Paul Theroux, Rebecca West and Herodotus”.

That got my attention for two reasons:

First, I realized that I had never heard of any of the writers mentioned, except Paul Theroux, and I had never read anything by him. Second, that there was probably a lot I could learn from them about the craft of describing travel and destinations.

We started this site to tell stories about food and travel. I’ve already learned how hard it is to describe the taste of food. Now I realized that I needed to up my game about travel writing, so I decided to start reading the best travel writers, beginning with Jan Morris. This was a serendipitous choice, because I found Jan Morris to be a fascinating person, in addition to being an excellent writer.

About Jan Morris

Jan Morris was a Welsh historian, author, and travel writer. She was born James Humphrey Morris on October 2, 1926. She published as James Morris until 1972, when she had gender reassignment surgery in Morocco.

Image source: theguardian.com

James Morris studied history at Christ Church, Oxford. He served in the 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers at the end of World War II. After the war, Morris was a correspondent for The Times (of London) and the Manchester Guardian.

James Morris was a member of the 1953 British Mount Everest Expedition, led by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzig Norgay. He was the only journalist on the expedition and though he was a novice, he climbed with the team to 22,000 feet.

When the expedition reached the summit, Morris sent a coded message to his editors at The Times of London. The message, which had been agreed upon in advance to protect their scoop, said “Snow conditions bad stop advanced base abandoned yesterday stop awaiting improvement.” It meant “Summit of Everest reached on 29 May by Hillary and Tenzing.” The message was carried by a runner from an ice field on Everest and then sent by wire to the editors in London. The Times published the announcement on June 2, 1953, the day of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation.

James Morris married Elizabeth Tuchniss in 1949. They lived together for over 50 years in a small village in North Wales. They divorced after Morris’ sex reassignment surgery, but remained together and later became civil partners when those partnerships were legalized in Wales.

Jan Morris’ major work was the Pax Britannica trilogy, a history of the British Commonwealth. Over the course of her life, she published over 40 books – travel narratives, histories, memoirs, and fiction.

Jan Morris died in 2020 at the age of 94. She was survived by Elizabeth and their four children.

Why Write or Read This Book

“Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere”* is a book that could only be written by someone with a deep love of history and an equally deep affection for Trieste. Jan Morris had both.

In the opening paragraph of the book, Morris describes Trieste in a way that seems to set low expectations for everything to follow.

[I]t is not one of your iconic cities, instantly visible in the memory or the imagination. It offers no unforgettable landmark, no universally familiar melody, no unmistakeable cuisine, hardly a single native name that everyone knows. It is a middle-sized, essentially middle-aged Italian seaport, ethnically ambivalent, historically confused, only intermittently prosperous, tucked away at the top right-hand corner of the Adriatic Sea, and so lacking the customary characteristics of Italy that in 1999 some 70 percent of Italians, so a poll claimed to discover, did not know it was in Italy at all.

So why take the time and energy necessary to write a book about such a lackluster place? For that matter, why take the time and energy to read a book like that?

For Jan Morris, the reason was the effect the city had on her. She first visited Trieste as James Morris, a 19 year old member of the British military at the end of World War II. “Ever since”, she wrote, “this city has curiously haunted me.” (p.16) Her memories of Trieste elicit “an unspecified yearning…what the Welsh language, in a well-loved word, calls hiraeth.”

The Portuguese have a similar word, saudade, which does not have a direct translation into English, but which one writer described as “a vague and constant desire for something that does not and probably cannot exist, for something other than the present, a turning towards the past or towards the future; not an active discontent or poignant sadness but an indolent dreaming wistfulness.”

Trieste was a place that Jan Morris returned to – physically and emotionally – throughout her life. It seems that it existed on two planes for her – the real (when she was there) and the imagined (when she was away). She studied its history, its culture, its geography, and its climate. This book, she said, was “a work partly of civic impressionism, but partly of introspection – or self-indulgence.” At the time she wrote it, she said it would be her last book. That turned out not to be true.

There were three reasons I wanted to read the book.

First, as mentioned earlier, I wanted to learn more about the craft and art of writing about places and journeys.

Second, I was intrigued by a description of the book I read in one review (now lost to me on the internet) that said, in essence, this book defies categorization.

And finally, I thought Jan Morris had lived a very interesting life and I wanted to hear her voice.

Those reasons aside, this might not have been the best book of hers to start with. Jan Morris seems to be trying to arrange or reconcile some aspects of her own life through her meditations on Trieste. I know very little about her life and work beyond what a few newspaper articles and her obituary tell. (Two such articles are linked below.) So until I read a few more of her books – “Spain” just arrived this week and “Conundrum”, her account of her transition from man to woman, is on my “to read” list – there are parts of this book that I may not have fully appreciated.

So while this review may lack some depth of understanding, I hope my appreciation for the author and her work comes through.

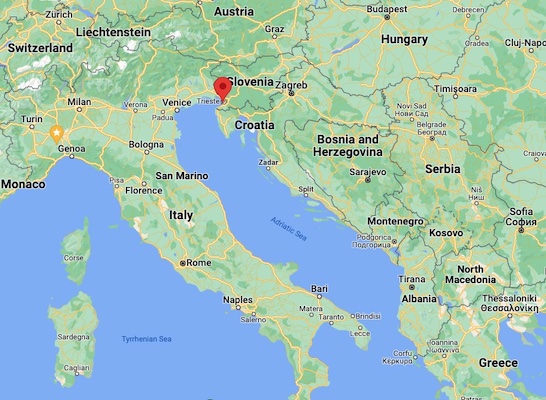

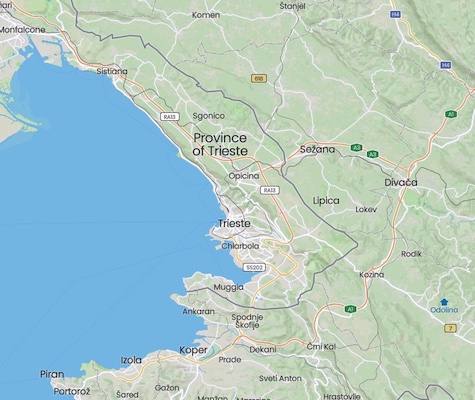

Where exactly is Trieste?

Morris described it as a place that existed “in the fold of the map”.

People who have never been here generally don’t know where it is. Visitors tend to leave it puzzled, and when they get home remember it with a vague sense of mystery, something they can’t put a finger on.

Map data (c) 2024 Google

Trieste is located at the northeast end of the Adriatic Sea, almost due east of Venice. A close look at the map reveals that it is just barely within the border of Italy – a border that moved frequently over the centuries. The border with Slovenia is five miles away. Croatia is ten miles to the south. Morris notes that “Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Hungary are all within a day’s drive.”

A Tangled History

Jan Morris had an encyclopedic knowledge of the history of the region. Throughout the book she weaves the history into the narrative. The simplest version is this: Trieste was colonized by the Romans and occupied at times by the Venetians. Napoleon occupied Trieste several times.

From the 14th to the early 20th centuries it was ruled by the Habsburg monarchy as part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Habsburgs built it into a prosperous port city. Morris devotes a lot of the book to this period, which appears to be, in her mind, the heyday of Trieste.

After the collapse of the Habsburg empire at the end of World War I, Trieste was again joined to Italy. When the Fascists came to power in 1922, they viewed Trieste as important “for the economic and political expansion of Italy in the Central Danube hinterlands”. It was annexed by the Germans near the end of World War II. For a brief period after WWII, it was a Free Territory, overseen by the United Nations until 1954, when the port city was again returned to Italy and the adjacent parts of the region were given to the then Yugoslavia.

The Book

This is not a travelog – a here’s-where-we-went-and-here’s-what-we-saw narrative. Morris is a knowledgeable and engaging guide. She organized the book in short chapters that focus on different aspects of Trieste and the surrounding region. Each chapter is a mix of history, descriptions of the current scene, personal reflections, and stories.

Painting a Picture with Words

The ability to describe a location is a basic requirement for any successful travel writer. Jan Morris does it with seeming ease, painting a broad picture, zooming in on the finer details, and bringing a touch of humor.

Image source: lelongweekend.com

Here is her description of the Grand Canal and its environs.

The city’s first eighteenth-century planners built a neat pattern of streets around a short canal, the Canal Grande, which intruded into the city from the sea and was to provide safe moorings for sea-going ships, whatever the weather. This arrangement is still a pleasure to discover. The canal runs inland for a few hundred yards from the bay, and it is only about thirty feet wide, but handsome Neo-classical buildings line it, and at the end there stands a dome church, with Ionic columns in a grand portico, which gives a touch of ceremony to the ensemble. The canal is full of small boats, almost all needing a lick of paint; three or four of the most derelict, hauled out of the water at the entrance to the canal, have been so splashed with vivid paints and graffiti, and are disposed so gracefully there, that they look like works of contemporary art. The canal quays are lively enough, if a bit shabby, and half-way up there is an outdoor market in a square, with mounds of fruit and vegetables, racks of dresses, flowers, socks and Mars bars.

Evoking the Glory Days

Jan Morris wrote several works of fiction, and her talent as a storyteller is apparent in the pages of Trieste. In the chapter titled “Only the Band Plays On”, she vividly imagines a scene taking place in the Piazza Unità, a large public square facing the sea, in 1897.

Image source: lelongweekend.com

Ocean liners and commercial ships are moored at the nearby docks. She is seated at an outdoor table at the Flora, one of four cafés on the piazza.

All around me first-class passengers, awaiting the time to board their ship, are enjoying their last half-hour on Austrian solid before sailing away to America, Alexandria or the east… There are splashes of colour everywhere – braids and gilded epaulets, bright silks of summer, gaudy parasols and pink fringed reticules.

A band is playing on a nearby bandstand, and “the music of a waltz sets people flirtatiously swaying as they chat.”

The harbor is alive with activity. The ocean liner Bohemia, built in Trieste, is about to leave on its maiden voyage.

Vessels of the Hungarian-Croatian line load up for Fiume and Spalato. Small steamboats with spindly funnels sail away to Grado, Venice or down the Istrian coast. Three-masters dry their sails in the roadsteads. Schooners from Greece or Sicily unload oranges or watermelons. Old black barges, with awnings and lines of washing, look like sampans in China, and Adriatic fishing-craft with red sails and blunt prows are painted with cabalistic symbols for luck.

When it is time to board the ship, “a smart seaman in blue and white hastens around the square ringing a bell, and with handshakes and salutes gradually the crowd disperses towards the quay…and the band speeds them on their way with a last lilting melody…”

Then Morris returns to the present day.

They are only shadows, now, though, these vestiges of Habsburg Trieste, like so much in this crepuscular city… As for the scenes in the Piazza Unità that day in 1897, I can hear the music still, but all the rest is phantom. The last passenger liner sailed long ago. The schooners, steamboats and barges have disappeared… The Caffè Flora changed its name to Nazionale when the opportunity arose, and is now defunct… Those silken and epauletted passengers, with all they represented, have vanished from the face of Europe, and I am left all alone listening to the band.

But what is the meaning of nowhere?

Early in the book, Jan Morris describes what she called “The Trieste Effect” – a moment “when a suggestion of Trieste is summoned so exactly into my consciousness that wherever I am, I feel myself transported there… It is as though I have been taken, for a brief sententious glimpse, out of time to nowhere.”

In those moments, Morris said the city appeared clearly to her and stirred up feelings of hiraeth, a “sweet melancholy [that] illustrates not just my adolescent emotions of the past, but my lifelong preoccupations, too.”

Trieste was for her, the “Capital of Nowhere”, an illusory Fourth World populated by people who, like her, felt like outsiders or “exiles in their own communities”. They transcend religion, race, age, wealth, and nationality and share common values like humor and understanding. As Morris put it

When you are among them you know you will not be mocked or resented, because they will not care about your race, your faith, your sex or your nationality, and they suffer fools if not gladly, at least sympathetically. They laugh easily. They are easily grateful. They are never mean. They are not inhibited by fashion, public opinion or political correctness. They are exiles in their own communities, because they are always in a minority, but they form a mighty nation, if they only knew it. It is the nation of nowhere, and I have come to think that its natural capital is Trieste.

The nation of Nowhere sounds like a pretty good place to be.

Hope for a brighter future

Toward the end of the book, Jan Morris notes that Trieste is a city “that was built ad-hoc – to be the principal port of a continental empire”. With the collapse of the Habsburg dynasty, Trieste lost its primary purpose and has struggled to find new ones. She says that the city has been “more or less stagnant” as long as she has known it. That sense of stagnation, of being a city in limbo, pervades Morris’ narrative.

But Morris saw hope for Trieste. She made her last visit to the city in 2000. At that time she saw signs of revitalization, with new initiatives in business, science, and the arts bringing new life to the city she loved. She did not expect to see it fully realized in her lifetime. That observation falls to those of us who can visit Trieste today and in the future, as I look forward to doing.

To read more about Jan Morris’ life and work, check out these articles:

“Jan Morris: ‘You’re talking to someone at the very end of things'”, by Tim Adams in The Guardian.

“A guide to the books of Jan Morris, a travel writer who tried to understand the meaning of everywhere”, by Sarah Barrell in National Geographic.

What interesting book have you read lately? Where did it take you? Leave a comment below or via the Contact Us form.

Until next week / Até a próxima semana

Mike

The Writer

* This link is direct to Amazon.com. At the time of this writing (July, 2022), we receive no affiliate payment if you buy a copy. If that changes in the future, we’ll let you know.

How fascinating!! I was in Trieste with my family in 1983. My dad

has a photo of my sister and me at an outdoor cafe on the grand canal. We were doing a grand tour of Venice, Florence, San Marino and their favorite Italian city – Riccione.

A little more on Jan Morris – https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/07/books/review/jan-morris-by-the-book.html?unlocked_article_code=AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAACEIPuonUktbcr4hlSlUbBCbfWt8ktVqciObOzaN7hHb4aS2SUyxD1KEfEs2c-0qIb61kZJ0zwzGfDpdnAYMYecZTnKVZLlA_DE6huIeFk5AIZCxv-IjtDjxrmpzEDL19rGTmNCywebwngezh5E6KYGHuC6PZ2GYzZ1ow-esTfl-p3XYOxqbGA7Q1joE4haF9c8g8ETQQZyCKvO3qDQF9P7iEZhLa6Qo3XoJJSG2Z3I7cu_9bLlIkWR-RR2h_4G089NpZJNkVWa_0JBMgc8D56q4DO_HidARXKLth1IuNR2KupA&smid=nytcore-ios-share