The story behind the story

Last fall we published a post titled “What Makes a Memorable Meal?” where we described the four attributes – food, service, ambience, and the people you’re with – that come together to make a meal an experience that you remember and talk about long after the day has passed.

In later posts, we invited you, our readers, to send us your stories of memorable meals. Our new friend Kirsten shared a story about a meal she had in Portugal over 45 years ago. And a short time later, our long-time friend Bob Battin sent us a story about a meal he remembered from his tour of duty in Vietnam.

Bob was drafted into the Army in 1968 and served as a combat medic. I asked him how he got that assignment, and he told me

[T]he Army requires you to take a battery of tests to determine where you would fit best. I remember taking these tests when I arrived at basic training. One test was mechanical aptitude, and I was killing it when it dawned on me that I did not want to work on Jeeps, tanks, or personnel carriers, so I changed several answers.

After basic training at Fort Cambell, Kentucky, Bob received 14 weeks of medical school at Fort Sam Houston, Texas. He was sent to Vietnam in September, 1968 – just weeks shy of his 21st birthday – and was assigned to an infantry unit – Company “C” (Charlie Company), 2/28th Infantry Battalion (“Black Lions of Cantigny”), 1st Infantry Division.

He was a platoon medic with 20 – 25 men in his platoon. He described his role, when treating wounded soldiers, this way:

Clearing the airway, stopping the bleeding, treating or preventing shock, and getting them on a dust-off was my primary focus. I carried five morphine syrettes; a syrette consists of a small tube of morphine with a hypodermic needle attached. You gave the wounded morphine except for a head or chest wound. You pinned the syrette to the wounded’s fatigue jacket so MASH units would recognize morphine treatment.

We met Bob years later, when he and Mike worked at the same company. Bob was in finance then. He told Mike that he began writing stories after he retired in 2008 to help deal with his memories from Vietnam and the emotions they evoke. He hopes to publish them in a book. We hope he will.

The story Bob shares below is different from any other we’ve published. Be forewarned: The language is graphic. But it fits in the context and reflects the reality that Bob and his fellow soldiers experienced. There are more memories here than just a meal.

Breakfast in the Boonies

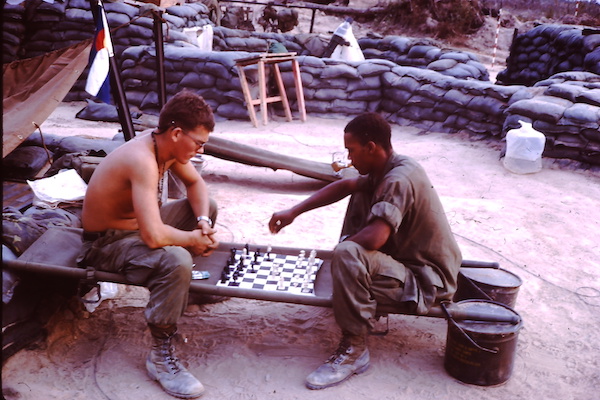

A young soldier prepares breakfast in Vietnam

by R. A. Battin

After a week or so in the boonies, you lose track of time and forget what day it is, not that it matters. What matters is that you are alive and well and not inside an aluminum flag-draped casket at Tan Son Nhut airbase waiting to be shipped home.

Charlie Company was operating out of a Fire Support Base named “Rita” near the Cambodian border, a few klicks from Loc Ninh village in Tay Ninh province. Real Indian country, full of NVA (North Vietnam Army) regulars. I wondered whose high-ranking officer’s relative gained the distinction of having a shithole FSB named after her. Some FSBs or NDPs (Night Defensive Positions) had historical names from the Division’s WWI or WWII battles, such as “Cantigny,” “Aachen,” or “Hurtgen.” Military locations in the States provided other names, such as “Junction City” (KS). Still others like “Rita” or “Julie,” I never understood the source. Maybe a division or battalion officer had a thing for Rita Hayworth or Julie Andrews.

The battalion had fallen into its usual routine at Rita. Each day, two of its three companies conducted a RIF (Reconnaissance-in-Force) while the remaining company stood down and secured the FSB. The following day, the company providing security rotated, so it was two consecutive days RIF humpin’, one day stand down.

From my perspective, a RIF gathers information about the enemy’s intentions, capabilities, and strengths. However, in reality, it was nothing more than a search and destroy mission, i.e., find the gooks, kill as many of them as you can and score a body count for the unit.

In ‘Nam, success was measured by the number of enemies killed, not by ground held, and it was all about the body count.

The stand-down days are somewhat dull, with not much going on until evening. Clean your weapon, write letters, read, play cards, and if you are a medic like me, attend to morning sick calls, and perform the usual sanitation duties of digging pit latrines and broadcasting diazinon to control the fly count. In the late afternoon, you learn if you are up for a night ambush. If selected, your stomach starts churning, and you begin to get your shit together. Clean your weapon again, gather ammo, claymore mines, smoke grenades, and fill your canteen from the water trailer. I will check my aid bag for medical supplies, ensuring I have Codeine tabs for uncontrollable coughs at the ambush site, a plentiful supply of combat dressings, and an ample supply of morphine syrettes for the wounded.

Charlie Company is standing down this morning, and my stomach is growling. Time to eat. I stare down at a brown, rectangular cardboard carton. It contains “C-Rations” or “Charlie Rats.” God, I’m sick of eating them and long for a decent hot meal and a real shower. It seems like every other day, the perennial unfavorite entre of “Ham and Lima Beans” finds me. Everyone in the platoon refers to it as “Ham and Motherfuckers” because the meal is detested and disgusting. It has been over a week since I last enjoyed a good meal, Beans, and Franks or Spaghetti and Meatballs. In between, I managed to keep down Beef and Potatoes, Boned Chicken, Boned Turkey, and Pork Steak, the latter with juices.

Staring back at me from the carton are three rows of print. Bold, black, capital block letters. The first reads, “MEAL, COMBAT, INDIVIDUAL.” The second row contains the meat or “M” unit, and the third row includes the name of the bread or “B” unit. Sometimes, a smaller line at the bottom describes the company that made the meal. Today’s carton is blank at the bottom, so my mind does not wander to the location of a “C-Ration” plant. However, the effort to make C-Rations weigh heavily on me. The carton required cutting trees; ink procured from somewhere, people slaughtered animals, picked and processed fruit and vegetables; the contents were canned, packaged, labeled, and shipped halfway around the world. I think about the people working in the packing department, and I wonder if they ever have thoughts that this may be a soldier’s last meal.

Each carton also contains a dessert or “D” unit, but the label lacks a description for this item. After eating so many “C-Rations,” you know which menus include your favorite dessert. I am partial to Sliced Peaches, Fruit Cocktail, Pound Cake, and Orange Nut Roll.

My favorite is Sliced Peaches, and my thoughts stray to an early childhood memory. It is the summer of 1953, and I am five years old, sitting on my grandfather’s knee in an Adirondack chair on his home’s small lawn.

My grandmother walks across the lawn toward my grandfather and me.

“Tobe, I thought you and Bobby would like a fresh peach.”

“Why, thank ‘ya, Gracie.” Reaching into his worn bib overalls pocket, he removes a small pocketknife with pearl inlays. He opens the blade and begins peeling the peach. The edge is worn thin from years of use, stained and caked with filth carving tobacco plugs my grandfather stuffs in his cheek. Holding the knife and peach in his large, gnarled hands, he begins cutting and removing small bites and inserting them in my mouth. I started gagging and coughing from the putrid taste of the tobacco. I try spitting, but my grandfather’s forefinger pushes my tongue back, forcing me to suppress, and swallow. Even though it seems like yesterday, the experience does not traumatize me to dislike peaches, only the disgusting taste and smell of tobacco juice and the sight of a dirty knife blade.

Image credit: Paul Mashburn on flickr.com

Inside the “C Ration” carton are four olive drab cans: one large, two small, and a flat one, packed upright. Depending on the menu, there is either a small or large can containing an “M” unit meat entree, a small “B” can containing crackers, cocoa powder, or candy, a small, flat spread can with jam, peanut butter, or cheese spread, and a “D” or dessert can compete with fruit or cake. Atop the “M” can is the flat can, and stacked next to them are the “B” and “D” cans. A brown foil pack and plastic spoon wrapped in cellophane are on top of the cans. Inside the foil, the pack is salt, pepper, sugar, instant coffee, non-dairy creamer, two pieces of Chiclet gum, toilet paper, a four-pack of cigarettes, and a book of moisture-proof matches. Everything a soldier needs for mealtime in the boonies in one neatly packed carton.

I wonder what kind of government process determines the “C” Ration carton label. Who thinks this shit up? Some government bureaucrat sitting amongst a row of gray Steelcase desks in an air-conditioned office in Washington, D.C. White, starched, short-sleeve shirt, with a pocket-protector shielding several pens and pencils; a clip-on tie, horn-rimmed glasses, polished shoes, probably smokes a pipe, the quintessential government bureaucrat. In his desk’s center drawer are neatly arranged pencils, pens, and paper clips.

“Let’s see; maybe we should label the Meat units “M.” The crackers, Bread “B,” and Desserts “D.”

This approach to governmental decision-making would require many meetings and discussions, the appointment of a large task force, numerous presentations, and several levels of management approval.

Brilliant, just plain fuckin’ bright.

Maybe I could trade places with him. He could come to ‘Nam, hump the boonies, participate in firefights and night ambushes, treat wounded GIs, zip KIA’s up in body bags, smoke pot, and enjoy dining on “C Rations.” I could sit behind his Steelcase desk in an air-conditioned office back in the world, study various ways to label “C” ration cartons, and line up pencils, pens, and paper clips in my desk drawer. After work, I could go home to my wife and kids in the evening and tune in to CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite. Bring the war into my living room.

“Let’s see; I think we should label this carton “Ham and Motherfuckers.”

The U.S. government has a systematic, well-organized, structured process and procedure for damn near everything, from conducting combat operations to a labeling system for a soldier’s food rations to constructing pit latrines and broadcasting diazinon powder. Hundreds of Standard Operating Procedure Manuals and Field Manuals document all of this and more.

Today’s breakfast carton reads “Chopped Ham and Eggs.” It contains a small “M” can, a small B-1 can of crackers, a spread can consisting of peanut butter, and a large “D” can of sliced peaches. At least, it’s not “Ham and Motherfuckers.” The brown foil pack has my favorite smokes, Winstons. I’m not wild about the crackers and peanut butter, but taken together with some Lomotil should help my dysentery contracted a few days ago from filling my canteen in a rice paddy.

Just another breakfast. Just another day humpin’ the boonies in ‘Nam, just another day trying to survive.

I say a short prayer to whoever, thankful to make it through the night and grateful that my platoon and Charlie Company are safe from harm’s way.

Hanging from a cord around my neck is a government-issued P-38 can opener. I flip open the blade and puncture the top of the “M” can, advancing the opener with a slow rocking motion, careful not to remove the lid entirely.

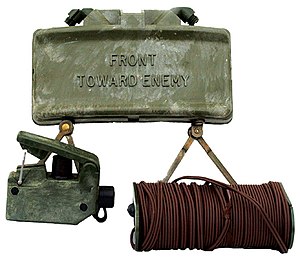

Image credit: trailspace.com

Selig, a skinny, blond-haired squad leader from South Dakota, is in an adjacent bunker.

“Hey, Selig, ‘got any C4?”

C4 is a block of plastic explosive, usually wrapped in cellophane. Engineers or demo teams use it to blow up bamboo clumps, tunnels, and anything requiring a shaped charge. We use it as fuel to heat our C-Rations. Our C4 supply source comes from the Claymore antipersonnel mines we carry.

electric blasting cap (front right)

Image credit: trailspace.com

Selig grabs a Claymore, opens the back of it with his bayonet, pinches off a chunk of the clay-like substance, and tosses it toward me.

“Here ‘ya go, Doc.”

“Thank ya’ kindly,” I say with a mid-air catch.

I knead and roll the C4 into a small ball and place it on the ground between my feet. Removing my Zippo, I squat down, spin the wheel and ignite the C4 creating a bright flash and a white-hot fire. Holding the “M” can by the lid, I slowly move breakfast back and forth over the sizzling flame, carefully avoiding the bituminous fumes.

A few minutes later, my platoon leader, Lt Montoya, call sign One Six, makes his morning rounds and approaches my bunker.

“We’re up for ‘bush tonight, Doc.”

“Morning, sir. Yes sir, OK, Six”.

Night Ambush. That’s great, just fuckin’ great. Another night ambush and I should have known. We did not go out today. Now, we’ll be out all night and RIF’n tomorrow.

Night ambush.

Immediately, my stomach starts to churn, and the anxiety builds. Staring down at the can of ham and eggs moving slowly over the flame, I pray this will not be my last breakfast.

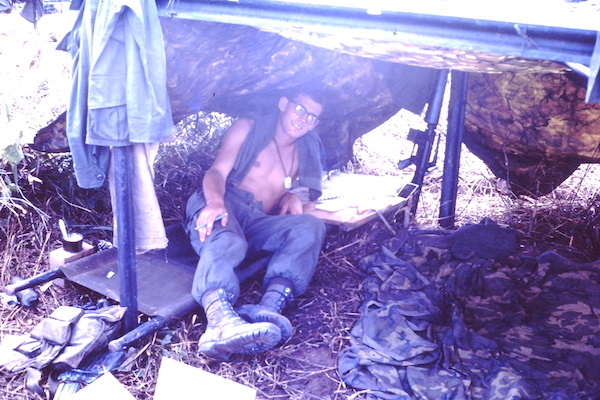

Unless otherwise noted, all photos are courtesy of Bob Battin.

What’s Your Story?

We send our thanks to Bob for sharing his story with us.

What’s the most memorable meal you’ve eaten? Tell us about it in an email to mike@thecookandthewriter.com. Don’t worry about polish. We’ll work with you to get it ready to publish.

Until next time / Até a próxima vez

Mary and Mike

The Cook and The Writer

I was a Sgt Combat Tracker Team Leader with the 4ID 64 Inf Platoon Camp Eneri.

We were issues Freeze dried LRP (Long Range Recon) meals. I liked Beef and Rice. I always carried a steel canteen cup to heat using a pinch of C4. We would get the C4 from prying open (very easy) a claymore mine. It looked and behaved like white clay. We would break off a small chunk when we knew we were going on long missions. C4 was great for heating the canteen cup in an open space. You did not want to inhale the fumes, I just turned my head away. The canteen cup would be boiling in seconds. The danger of using C4 for cooking was low. You would need great pressure or a blasting cap and charger to detonate. All the units our team worked for in the Central Highlands cooked with C4. Other good tasting LRP meals were spaghetti and meat sauce, Pork rice and pineapple and beef stew. Also the dried chocolate candy bars were great.

Many thanks, Mike and Mary, for publishing my short story “Breakfast in the Boonies”, very much appreciated, and many thanks to your subscribers for their insightful and thoughtful comments.

Haunting memories from such a young age, lasting a lifetime. Thanks so much for posting this story, and to Bob Battin for telling it. Heartfelt gratitude for his service and for all those who served and are serving today. Stories from men such as Bob need to be told and remembered..

Well….my DD214 says I am a Vietnam Vet but serving my time in the USAF I wasn’t subjected to the daily routine as described. Thanks to those that served and will serve. May God Bless them all.

Hi Mary and Mike….before reading Bob’s story I thought I might write you about the “MRE” government provided memorable meals I ate in my home with a fallen tree covering the bedroom side of the house and a blue plastic roof ineffective in preventing the rain from dripping all over the place on the other side…all because Hurricane Ivan had just roared through the gulf coast of Alabama (September, 2004).

Although it was unpleasant eating that stuff in a hot, humid kitchen with broken glass and rubble everywhere, compared to Bob’s experience in Vietnam my dining was like enjoying a meal fit for a queen sans the churning in my stomach because I might have to go out in the dark at night and kill people or be killed!

Wow. Thank you so much for sharing this. And thank you to Bob Battin and Doc King and so, so, so many others for their service. This was an eye-opener.