Introduction

If you visit Lisbon for a short stay, say 3 days to a week, you probably won’t get around to visiting the Museu de Marinha – the Maritime Museum. I have never seen it on any of the “Top 10 Things To Do In Lisbon” lists.

But if you’re here longer, and you’ve already seen the Monument to the Discoveries, listened to some fado music in Alfama, tried and failed to translate saudade, and learned a bit about Portugal’s seafaring past, then the Maritime Museum is a great place to go.

The Maritime Museum is not a place you’d stumble on by accident, even though it’s hiding in plain sight at the far west end of the Jerónimos Monastery. The natural flow of pedestrian traffic in the touristy district of Belém moves toward the center entrance of the Monastery and then back eastward toward the famous pasteis shop and other attractions. But walk to the end of the building, turn right and you’re at the entrance.

Origins of the Museum

In 1863, Dom Luis I, King of Portugal from 1861 – 1889, began collecting items that represented Portugal’s maritime history. His collection was enlarged over the years and became the basis for the museum, which opened 100 years later, in 1963.

Today the the museum’s collection includes over 23,000 items.

Our Tour

A few weeks ago, Mary signed us up for a guided tour of the museum, an event organized by the International Women in Portugal, a group she recently joined. We had never heard of the museum and were curious about what we might see and learn there.

It turned out to be a fascinating experience that gave us a deeper understanding of Portuguese history and also provided some surprising connections to our experience as US citizens living abroad.

So on a bright, warm March morning, we joined a group of about 25 people – mostly women, but a few “plus ones” as well – at the door to the museum. In the courtyard behind us several groups of school children sat in circles on the paving stones. We guessed they were on a field trip to the planetarium next door. Their excited energy was contagious. They were out of school, on a field trip! And even though grade school is a distant memory for us, we felt like we were on a field trip, too!

Our guide, Ines, introduced herself and led us into the building. Throughout the 2 1/2 hour tour, she proved to be an excellent guide. She was knowledgeable about the history surrounding the items on display. She moved us through the museum, stopping to explain the more significant displays. Her comments gave us both the specifics of a particular piece, but also something about its historical or social context. All of it lightened by her good nature and sense of humor.

And she slipped in a couple of present day political references that had unexpected resonance with life in the United States.

What We Saw

Is that Prince Henry?

Our tour began in a wide gallery dominated by a statue of Prince Henry the Navigator, the royal sponsor and instigator of most of the voyages made by Portuguese explorers in the 15th century.

Ines made the point that even though the statue presented a familiar image of Prince Henry, including his broad-brimmed hat, it was still a guess, as there are no known images of him. (We had learned that during an earlier visit to the National Museum of Antique Art, where a similar image of Prince Henry is found in the “St. Vincent Panels” and is accompanied by scholarly debate about its accuracy.)

She went on to say that the period from the 15th to the 17th centuries, typically referred to as “the Age of Discoveries”, should really be called “the Age of Expansion”. Portugal’s land borders had been defined in a treaty with Spain, she explained. Surrounded by Spain on two sides, the sea was the only route for expansion.

“This is not being woke, trying to rewrite history like some people are trying to do in the USA”, she said, using a phrase that caught our attention. “It’s just being historically accurate”.

Exploring the World

The museum is organized in three main areas. The first one we entered was made up of artifacts that traced the history of the Portuguese navigators in the “Age of Discoveries” (or “Expansion”).

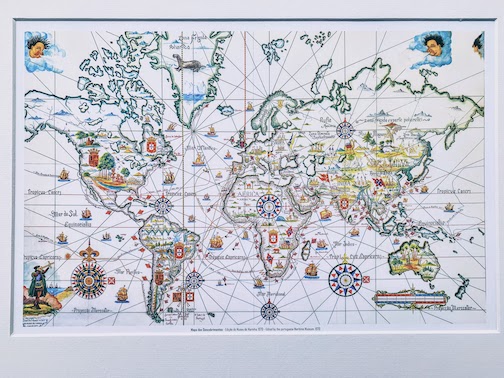

There were several large maps that traced the voyages of the early explorers – Bartholomew Dias, Vasco da Gama, and others – who left Portugal in small ships to find new routes around the horn of Africa and on to India and the Far East.

A few cases held detailed models of the ships that the Portuguese explorers used. Some of the models were almost 5 feet tall, but they still looked like very small boats to travel on a wild, uncharted ocean.

A variety of navigation instruments were also displayed. These included the astrolabe, a device that allowed sailors to calculate their ship’s position by measuring the location of the stars. Ines referred to it as “the father of the GPS”.

Also on display was a large armillary sphere, a large metal cage that represented the cosmos, with earth in the center. Ines pointed out that the crest of Portugal includes an an armillary sphere, which represented political, economic, and maritime power.

The dark side of the sea trade

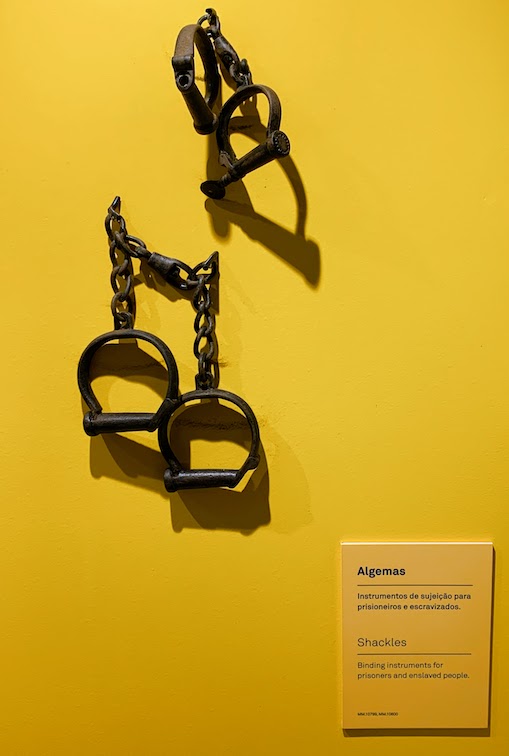

Near the end of the first section of the museum, Ines stopped to point out a small panel from which hung two metal chains with rings like stirrups on each end. They were shackles used to restrain Africans being transported on slave ships. She said that it’s estimated that 3/4 of the Africans carried into slavery rode on Portuguese ships.

In 1761, the Marquês de Pombal outlawed slavery – prohibiting any slave traffic to enter Portugal. It took over 100 years before slavery was outlawed in all nations of the Portuguese empire.

Ines paused and looked at us, then said, “We can’t forget that Portugal was a major participant in the slave trade.”

That statement made us stop and think about the contrast to the current controversy in the US about teaching Black History – or what one scholar called an attempted “erasure of Black History”.

Moving to the present day

The second area of the museum was a long hall filled with display cases, freestanding artifacts, and paintings that showed the progression of Portuguese naval and commercial activities up to the present day. We didn’t spend much time in this area, so it’s one that we’ll have to revisit on another day.

The big stuff

The final section of the museum was a large area the size of an airplane hangar where the largest items in the collection were on display.

The first thing we saw as we entered was the gilded stern of the royal barge Sirius. It was built in 1778 at the Royal Naval Shipyard in Lisbon by order of Queen Maria I. It served various functions for the royal house until 1957, when, on its last voyage, it transported Queen Elisabeth II of England on the Tagus River.

We had to walk around to the side of the barge to see just how large it was. The Sirius is 29 meters (95 feet) long and had seats for 80 oarsmen.

Viewed from above, you can see the overall proportions – most of the boat is used by the guys doing the rowing.

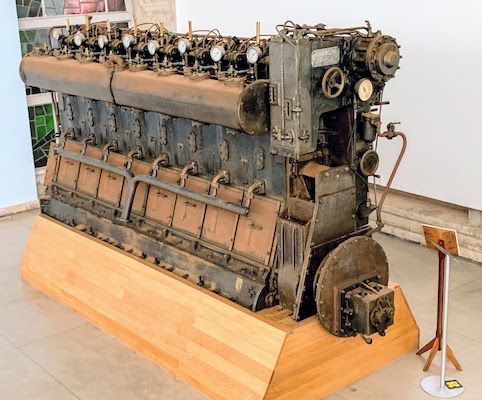

I worked for an engine company for 30 years, so I had to stop and take a close look at this one. It’s a 750hp diesel built by MAN in Germany for the Albert Leo Schlageter, a ship built in Hamburg in 1937. The ship, later renamed Sagres, was acquired by the Portuguese navy in 1962 and has been used since then as a training ship.

One of the last things we saw before leaving was the oldest Portuguese aircraft in a museum anywhere. The FBA Type III “Schreck” was used by the Portuguese navy for coastal surveillance until 1918. There are only three of these planes left in the world.

The other thing about a great guide

We’ve found that all great guides leave you wanting to know more at the end of the tour. We finished our visit to the Maritime Museum with sore feet and an appreciation for all that we had seen. But we also want to come back and spend more time on our own, looking and learning.

Until next time / Até a próxima vez

Mary and Mike

The Cook and The Writer

What’s your favorite museum and why? Tell us about your last visit with a note in the comments below or via the Contact Us form.

Hi we are considering a trip to Portugal in April. This is number 1 on a friend’s priority list. What are the opening hours? Days?

Thank you so much for taking us along on your great adventure. It’s always a joy. 🥰

What a great commentary. Especially the comments from the guide regarding “woke”. Living abroad is a great way to re-discover our own history.

Very cool! David would love it!

Hi Mike and Mary! We were on the tour as well, and I wish I had known you were there so I could tell you how much I enjoy your blog posts. I hope I’ll get to meet you both at another time. By the way, your summary of the tour was excellent and we too thought Ines did a great job.

Wow, isn’t that place fabulous! We discovered it ourselves by accident a couple summers ago when we took some visitors to see the monastery. The line was long and the sun was hot, so we decided to wander around the west end to the Maritime Museum where there was no line and very few visitors. And, WOW, we were delighted! We need to return for a more in depth tour.

David